Emma Humphries, Queen’s University Belfast

Linguistic prescriptivism is all around us, whether we realise it or not.

In its simplest form, prescriptivism is both an ideology which posits that there are right and wrong, correct and incorrect, good and bad ways of using language, and the actual activity of insisting that the ‘correct’, ‘right’ and ‘good’ forms are used.

Beyond the binary of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ in language, many other judgements and assumed characteristics are associated with how a person writes, speaks or signs a language: their intelligence, their age, where they’re from, their social class. I’ve even seen grammar use linked to musical taste: only a Justin Bieber fan would use that construction.

We know that prescriptivism can be found in grammar books and dictionaries and – as the Bridging the Unbridgeable project continues to show – in usage guides. All those texts are designed to instruct people on how to use their language, and we can safely assume that a reader seeking out a usage guide is looking for instruction on how to use their language. A certain level of prescriptivism is expected, or at least not surprising, in these publications.

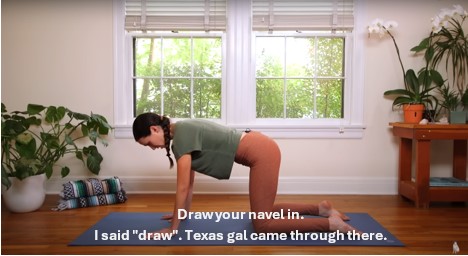

But prescriptivism is much more far-reaching than this. In fact, once you start looking for it, you begin to notice it in all aspects of your everyday life. It’s in the films and series that we watch, the music, podcasts and radio programmes that we listen to, in the books, magazines and newspapers that we read. I can’t even escape it in my trusty Yoga with Adriene YouTube videos.

Adriene corrects her own pronunciation of the word draw (at 2:14 into the video)

Prescriptivism in these popular culture forms is not necessarily expected. I certainly wasn’t looking for language advice or judgements along with my downward dog. And yet, there it is. This makes prescriptivism rather unavoidable. It’s not just in the publications that we are actively accessing for language advice, but right there in our usual reading, writing and listening material. Often, it’s a quick, flyaway comment, perhaps passing by unnoticed, or at least less noticed than the prescriptivism we might have come to expect in style guides and grammars.

For instance, two examples are found in one of the highest grossing films of 2024, Wicked.

Glinda: I could care less what others think.

Elphaba: Couldn’t.

Glinda: What?

Elphaba: You couldn’t care less what other people think. Though, I… I doubt that.

Elphaba similarly corrects Glinda’s use of ‘good’ in one of the film and musical’s famous lines: ‘Pink goes good with green’. The audience of this double Oscar winning film, and consequently its prescriptivism, is massive.

Apart from the popular culture outputs we consume, prescriptivism is also found in the linguistic landscape of our general surroundings: on signs, posters, and graffiti. The image below was taken in a pub in England.

English pub sign with language correction (© Emma Humphries)

Prescriptivism in popular culture reaches a potentially massive audience. Whereas traditional prescriptivist texts are often accessed purposefully by a limited stratum of society, popular culture prescriptivism can reach the masses. Similarly, although much more localised, prescriptivism in the linguistic landscape runs through our everyday lives, whilst we’re out and about just living our lives.

When we study prescriptivism in any form, it can help us to uncover the systems of power that influence certain language beliefs and behaviours, particularly those which may silence or exclude certain people. Using language ‘correctly’ is seen as valuable – to use Bourdieu’s (1982) term, it has cultural capital – and people who fall short of this expected ‘correct’ use are often judged negatively. These judgements have inevitable consequences for diversity, as the way we speak, write and sign reflects parts of who we are, like where we’re from, our gender, or our ethnicity.

With prescriptivism often going unquestioned, the associated judgements and social consequences, including reduced potential for social mobility and respect for diversity (Paveau and Rosier 2008), also often go unquestioned. Understanding how prescriptivism spreads in society, including through popular culture, is key to tackling entrenched issues like language-based prejudice and discrimination, and the broader related social challenges such as structural racism and sexism.

To understand the presence and spread of prescriptivism in popular culture, we need data, i.e. lots of examples! This is what my new project aims to collect, and I’d love your help!

Your Wrong is a crowdsourced database of examples of prescriptivism in any form of popular culture and in any language.

If, during your usual reading, watching and listening habits, you notice either:

a) an example of linguistic correction;

b) a judgement (be that positive or negative) about language use; or

c) descriptions of people or characters as being prescriptive or pedantic

in any form of popular culture, in any language, I’d be hugely grateful if you could let me know via the website. The call will be open for at least the length of the project (until October 2027).

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1982. Ce que parler veut dire. L’économie des échanges linguistiques. Paris: Fayard.

Paveau, Marie-Anne, and Laurence Rosier. 2008. La langue française : passions et polémiques. Paris: Vuibert.